By: Alexander Shatrov

Geovis Project Assignment @RyersonGeo, SA8905, Fall 2018.

Intro:

The topic of this geovisualization project is the TTC. More specifically, the Toronto subway system and its many, many, MANY delays. As someone who frequently has to suffer through them, I decided to turn this misfortune into something productive and informative, as well as something that would give a person not from Toronto an accurate image of what using the TTC on a daily basis is like. A time-series map showing every single delay the TTC went through over a specified time period. The software chosen for this task was Carto, due to its reputation as being good at creating time-series maps.

Obtaining the data:

First, an excel file of TTC subway delays was obtained from Toronto Open Data, where it is organised by month, with this project specifically using August 2018 data. Unfortunately, this data did not include XY coordinates or specific addresses, which made geocoding it difficult. Next, a shapefile of subway lines and stations was obtained from a website called the “Unofficial TTC Geospatial Data”. Unfortunately, this data was incomplete as it had last been updated in 2012 and therefore did not include the recent 2017 expansion to the Yonge-University-Spadina line. A partial shapefile of it was obtained from DMTI, but it was not complete. To get around this, the csv file of the stations shapefile was opened up, the new stations added, the latitude-longitude coordinates for all of the stations manually entered in, and the csv file then geocoded in ArcGIS using its “Display XY Data” function to make sure the points were correctly geocoded. Once the XY data was confirmed to be working, the delay excel file was saved as a csv file, and had the station data joined with it. Now, it had a list of both the delays and XY coordinates to go with those delays. Unfortunately, not all of the delays were usable, as about a quarter of them had not been logged with a specific station name but rather the overall line on which the delay happened. These delays were discarded as there was no way to know where exactly on the line they happened. Once this was done, a time-stamp column was created using the day and timeinday columns in the csv file.

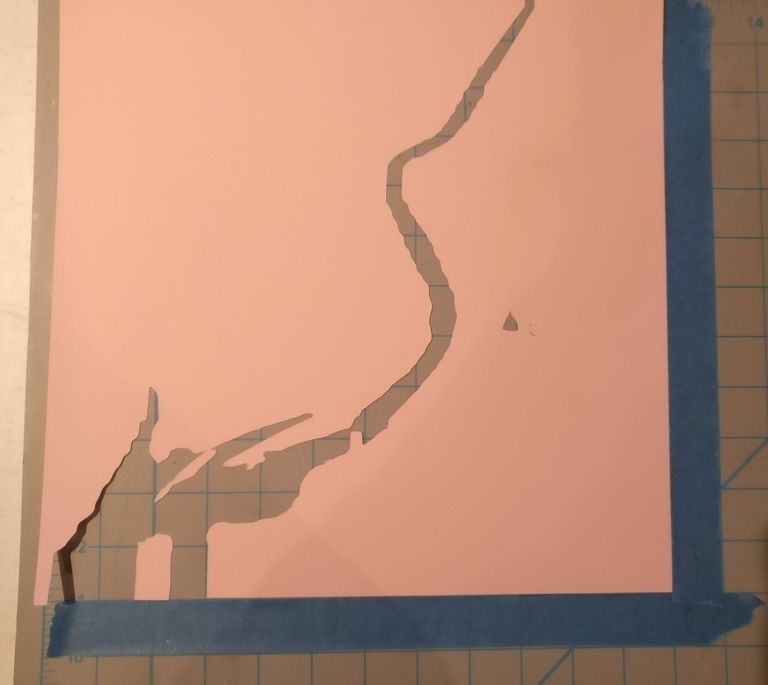

Finally, the CSV file was uploaded to Carto, where its locations were geocoded using Carto’s geocode tool, seen below.

It should be noted that the csv file was uploaded instead of the already geocoded shapefile because exporting the shapefile would cause an issue with the timestamp, specifically it would delete the hours and minutes from the time stamp, leaving only the month and day. No solution to this was found so the csv file was used instead. The subway lines were then added as well, although the part of the recent extension that was still missing had to be manually drawn. Technically speaking the delays were already arranged in chronological order, but creating a time series map just based on the order made it difficult to determine what day of the month or time of day the delay occurred at. This is where the timestamp column came in. While Carto at first did not recognize the created timestamp, due to it being saved as a string, another column was created and the string timestamp data used to create the actual timestamp.

Creating the map:

Now, the data was fully ready to be turned into a time-series map. Carto has greatly simplified the process of map creation since their early days. Simply clicking on the layer that needs to be mapped provides a collection of tabs such as data and analysis. In order to create the map, the style tab was clicked on, and the animation aggregation method was selected.

The color of the points was chosen based on value, with the value being set to the code column, which indicates what the reason for each delay was. The actual column used was the timestamp column, and options like duration (how long the animation runs for, in this case the maximum time limit of 60 seconds) and trails (how long each event remains on the map, in this case set to just 2 to keep the animation fast-paced). In order to properly separate the animation into specific days, the time-series widget was added in the widget tab, located next to to the layer tab.

In the widget, the timestamp column was selected as the data source, the correct time zone was set, and the day bucket was chosen. Everything else was left as default.

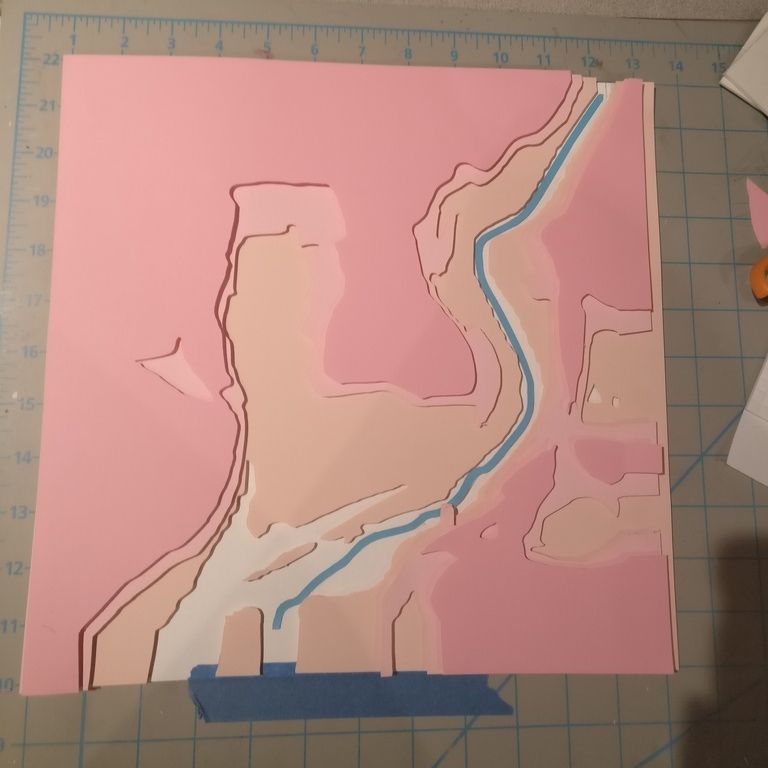

The buckets option is there to select what time unit will be used for your time series. In theory, it is supposed to range from minutes to decades, but at the time of this project being completed, for some reason the smallest time unit available is day. This was part of the reason why the timestamp column is useful, as without it the limitations of the bucket in the time-series widget would have resulted in the map being nothing more then a giant pulse of every delay that happened that day once a day. With the time-stamp column, the animation feature in the style tab was able to create a chronological animation of all of the delays which, when paired with the widget was able to say what day a delay occurred, although the lack of an hour bucket meant that figuring out which part of the day a delay occurred requires a degree of guesswork based on where the indicator is, as seen below

Finally, a legend needed to be created so that a viewer can see what each color is supposed to mean. Since the different colors of the points are based on the incident code, this was put into a custom legend, which was created in the legend tab found in the same toolbar as style. Unfortunately this proved impossible as the TTC has close to 200 different codes for various situations, so the legend only included the top 10 most common types and an “other” category encompassing all others.

And that is all it took to create an interesting and informative time-series map. As you can see, there was no coding involved. A few years ago, doing this map would have likely required a degree of coding, but Carto has been making an effort to make its software easy to learn and easy to use. The result of the actions described here can be seen below.

https://alexandershatrov.carto.com/builder/8574ffc2-9751-49ad-bd98-e2ab5c8396bb/embed

>>>>>>>>>>>

>>>>>>>>>>>

Once all the coding and testing was completed, running the app was simple. I was able to bundle my code and send it to my personal phone, a Galaxy S9. The functions called the hosted service layers and displayed them in the map (Wifi or internet connection was required). I was also able to click on neighbourhoods and it would open my second activity that displayed the attribute information of that neighbourhood. If you want a more in-depth look at my code, it is available at https://github.com/jclovie/GeoVis-Ryerson/.

Once all the coding and testing was completed, running the app was simple. I was able to bundle my code and send it to my personal phone, a Galaxy S9. The functions called the hosted service layers and displayed them in the map (Wifi or internet connection was required). I was also able to click on neighbourhoods and it would open my second activity that displayed the attribute information of that neighbourhood. If you want a more in-depth look at my code, it is available at https://github.com/jclovie/GeoVis-Ryerson/.