1. Introduction and Objectives

This report documents the methodology and execution of a geospatial analysis aimed at identifying specific segments of the road network with a high potential for dangerous solar glare during critical commute times.

The analysis focuses on the high-risk window for solar glare in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), typically the winter months (January) around the afternoon commute (4:00 PM EST), when the sun is low on the horizon and positioned in the southwest.

The primary objectives were to:

1. Calculate the average solar position (Azimuth and Elevation) for the defined high-risk period.

2. Determine the orientation (Azimuth) of all road segments in the StreetCentreline layer.

3. Calculate the acute angle between the road and the sun (R_S_ANGLE).

4. Filter the results to identify segments where the road is both highly aligned with the sun and the driver is traveling into the solar direction, marking them as High Glare Hazard Potential.

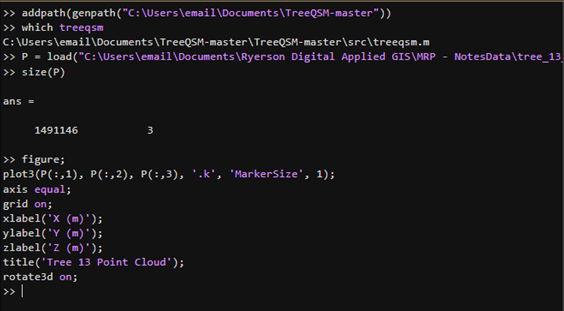

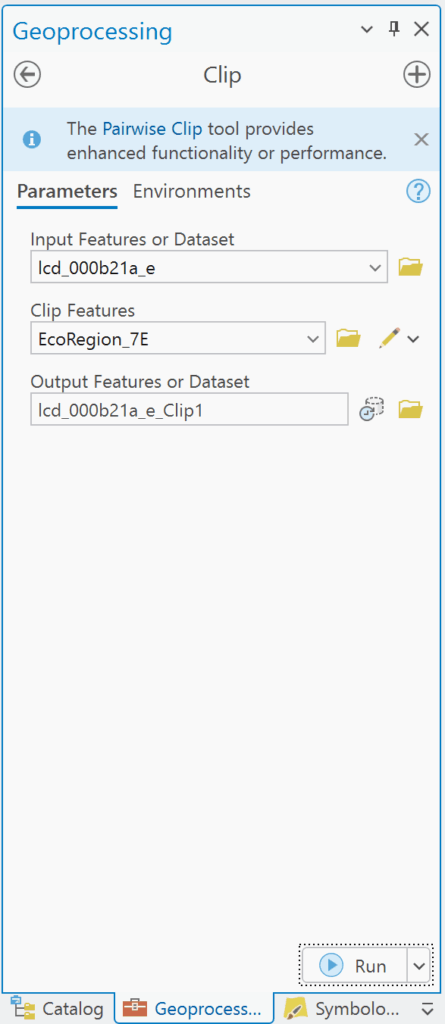

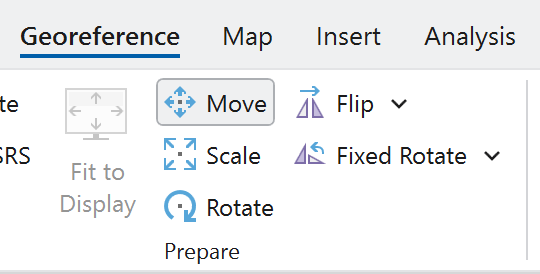

2. Phase I: ArcPy Scripting for Data Calculation

The first phase involved developing an ArcPy script to calculate the necessary astronomical and geometric values and append them to the input feature class. Due to database constraints (specifically the 10-character field name limit in certain geodatabase formats), field names were abbreviated.

2.1. Script Parameters and Solar Calculation

The script uses the approximate latitude and longitude of Mississauga, ON (43.59, -79.64), and calculates the average solar position for the first week of January 2025 at 4:00 PM EST.

2.2. Final ArcPy Script

The following Python code was executed in the ArcGIS Pro Python environment:

import arcpy

import datetime

import math

import calendar

# — User Inputs (ADJUST THESE VALUES AS NEEDED) —

input_fc = “StreetCentreline”

MISSISSAUGA_LAT = 43.59

MISSISSAUGA_LON = -79.64

TARGET_TIME_HOUR = 16

YEAR = 2025

# — Field Names for Output (MAX 10 CHARACTERS FOR COMPLIANCE) —

ROAD_AZIMUTH_FIELD = “R_AZIMUTH” # Road segment’s direction (Calculated)

SOLAR_AZIMUTH_FIELD = “S_AZIMUTH” # Average Sun direction

SOLAR_ELEVATION_FIELD = “S_ELEV” # Average Sun altitude

ROAD_SOLAR_ANGLE_FIELD = “R_S_ANGLE” # Angle difference (Glare Indicator: 0=Worst Glare)

# — Helper Functions (Solar Geometry and Segment Azimuth) —

def calculate_solar_position(lat, lon, dt_local):

“””Calculates Solar Azimuth and Elevation (Simplified NOAA Standard).”””

TIMEZONE = -5

day_of_year = dt_local.timetuple().tm_yday

gamma = (2 * math.pi / 365) * (day_of_year – 1 + (dt_local.hour – 12) / 24)

eqtime = 229.18 * (0.000075 + 0.001868 * math.cos(gamma) – 0.032077 * math.sin(gamma)

– 0.014615 * math.cos(2 * gamma) – 0.040849 * math.sin(2 * gamma))

decl = math.radians(0.006918 – 0.399912 * math.cos(gamma) + 0.070257 * math.sin(gamma)

– 0.006758 * math.cos(2 * gamma) + 0.000907 * math.sin(2 * gamma)

– 0.002697 * math.cos(3 * gamma) + 0.00148 * math.sin(3 * gamma))

time_offset = eqtime + 4 * lon – 60 * TIMEZONE

tst = dt_local.hour * 60 + dt_local.minute + dt_local.second / 60 + time_offset

ha_deg = (tst / 4) – 180

ha_rad = math.radians(ha_deg)

lat_rad = math.radians(lat)

cos_zenith = (math.sin(lat_rad) * math.sin(decl) +

math.cos(lat_rad) * math.cos(decl) * math.cos(ha_rad))

zenith_rad = math.acos(min(max(cos_zenith, -1.0), 1.0))

solar_elevation = 90 – math.degrees(zenith_rad)

azimuth_num = -math.sin(ha_rad)

azimuth_den = math.tan(decl) * math.cos(lat_rad) – math.sin(lat_rad) * math.cos(ha_rad)

if azimuth_den == 0:

solar_azimuth_deg = 180 if ha_deg > 0 else 0

else:

solar_azimuth_rad = math.atan2(azimuth_num, azimuth_den)

solar_azimuth_deg = math.degrees(solar_azimuth_rad)

solar_azimuth = (solar_azimuth_deg + 360) % 360

return solar_azimuth, solar_elevation

def calculate_segment_azimuth(first_pt, last_pt):

“””Calculates the azimuth/bearing of a line segment.”””

dx = last_pt.X – first_pt.X

dy = last_pt.Y – first_pt.Y

bearing_rad = math.atan2(dx, dy)

bearing_deg = math.degrees(bearing_rad)

azimuth = (bearing_deg + 360) % 360

return azimuth

# — Main Script Execution —

arcpy.env.overwriteOutput = True

try:

# 1. Calculate Average Solar Position

start_date = datetime.date(YEAR, 1, 1)

end_date = datetime.date(YEAR, 1, 7)

total_azimuth, total_elevation, day_count = 0, 0, 0

current_date = start_date

while current_date <= end_date:

local_dt = datetime.datetime(current_date.year, current_date.month, current_date.day, TARGET_TIME_HOUR, 0, 0)

az, el = calculate_solar_position(MISSISSAUGA_LAT, MISSISSAUGA_LON, local_dt)

if el > 0:

total_azimuth += az

total_elevation += el

day_count += 1

current_date += datetime.timedelta(days=1)

if day_count == 0:

raise ValueError(“The sun is below the horizon for all calculated dates/times.”)

avg_solar_azimuth = total_azimuth / day_count

avg_solar_elevation = total_elevation / day_count

# 2. Add required fields

for field_name in [ROAD_AZIMUTH_FIELD, SOLAR_AZIMUTH_FIELD, SOLAR_ELEVATION_FIELD, ROAD_SOLAR_ANGLE_FIELD]:

if not arcpy.ListFields(input_fc, field_name):

arcpy.AddField_management(input_fc, field_name, “DOUBLE”)

# 3. Use an UpdateCursor to calculate and populate fields

fields = [“SHAPE@”, ROAD_AZIMUTH_FIELD, SOLAR_AZIMUTH_FIELD, SOLAR_ELEVATION_FIELD, ROAD_SOLAR_ANGLE_FIELD]

with arcpy.da.UpdateCursor(input_fc, fields) as cursor:

for row in cursor:

geometry = row[0]

segment_azimuth = None

if geometry and geometry.partCount > 0 and geometry.getPart(0).count > 1:

segment_azimuth = calculate_segment_azimuth(geometry.firstPoint, geometry.lastPoint)

road_solar_angle = None

if segment_azimuth is not None:

angle_diff = abs(segment_azimuth – avg_solar_azimuth)

road_solar_angle = min(angle_diff, 360 – angle_diff) # Acute angle (0-90)

row[1] = segment_azimuth

row[2] = avg_solar_azimuth

row[3] = avg_solar_elevation

row[4] = road_solar_angle

cursor.updateRow(row)

except arcpy.ExecuteError:

arcpy.AddError(arcpy.GetMessages(2))

except Exception as e:

print(f”An unexpected error occurred: {e}”)

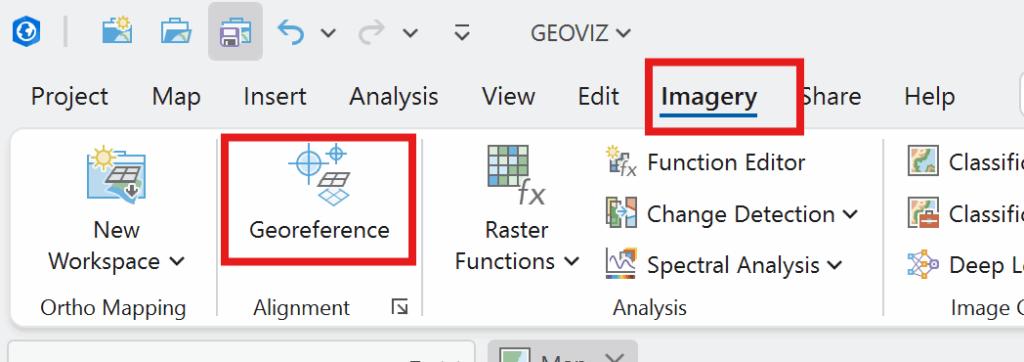

3. Phase II: Classification of True Hazard Potential (Arcade)

Calculating the R_S_ANGLE ($0^\circ$ to $90^\circ$) identifies road segments that are geometrically aligned with the sun. However, it does not distinguish between a driver traveling into the sun (High Hazard) versus traveling away from the sun (No Hazard).

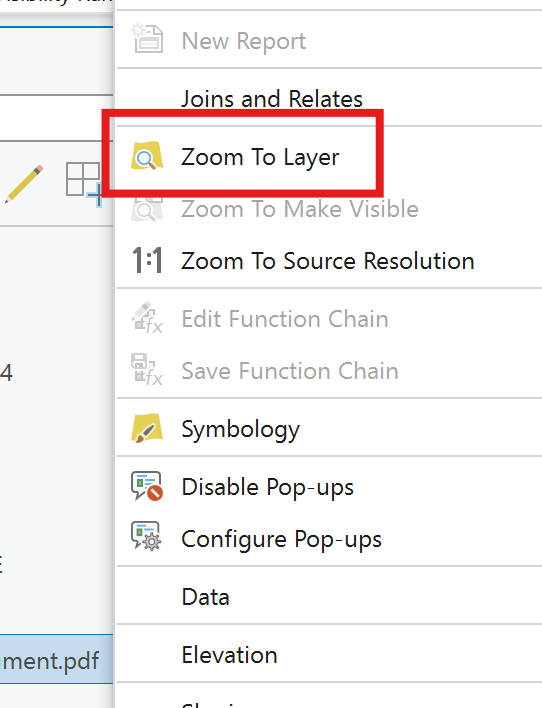

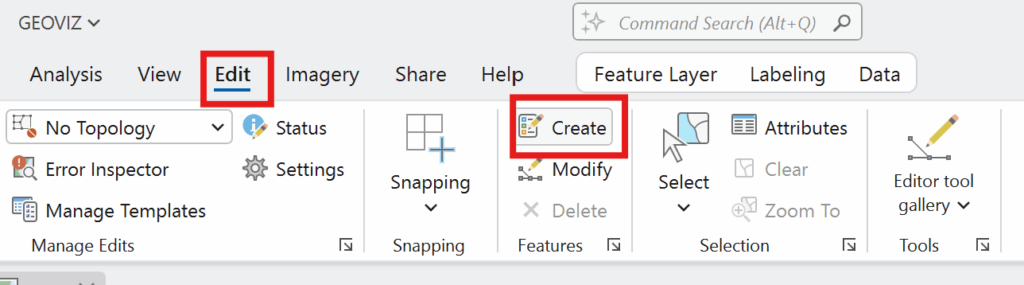

To isolate the segments with a true hazard potential, a new field (HAZARD_DIR) was created and calculated using an Arcade Expression in ArcGIS Pro’s Calculate Field tool.

3.1. Classification Criteria

A segment is classified as having High Hazard Potential (HAZARD_DIR = 1) if both conditions are met:

1. Angle Alignment: The calculated R_S_ANGLE is $15^\circ$ or less (indicating maximum glare).

2. Directional Alignment: The segment’s azimuth (R_AZIMUTH) is oriented within $\pm 90^\circ$ of the sun’s azimuth (S_AZIMUTH), meaning the driver is facing the sun.

3.2. Final Arcade Expression for Field Calculation

The following Arcade script was used to populate the HAZARD_DIR field (Short Integer type):

// HAZARD_DIR Field Calculation (Language: Arcade)

// Define required input fields

var solarAz = $feature.S_AZIMUTH; // Average Sun Azimuth (e.g., 245 degrees)

var roadAz = $feature.R_AZIMUTH; // Road Segment Azimuth (0-360)

var angleDiff = $feature.R_S_ANGLE; // Acute Angle between Road and Sun (0-90)

// 1. Check for High Glare Angle (< 15 degrees)

if (angleDiff <= 15) {

// 2. Check if the road direction is facing INTO the solar direction

// Calculate the acute difference between roadAz and solarAz (0-180 degrees)

var directionDiff = Abs(roadAz – solarAz);

var acuteDirDiff = Min(directionDiff, 360 – directionDiff);

// If the difference is <= 90 degrees, the driver is generally facing the sun

if (acuteDirDiff <= 90) {

return 1; // TRUE: HIGH Glare Hazard Potential

}

}

return 0; // FALSE: NO Glare Hazard Potential (Angle too high or driving away from sun)

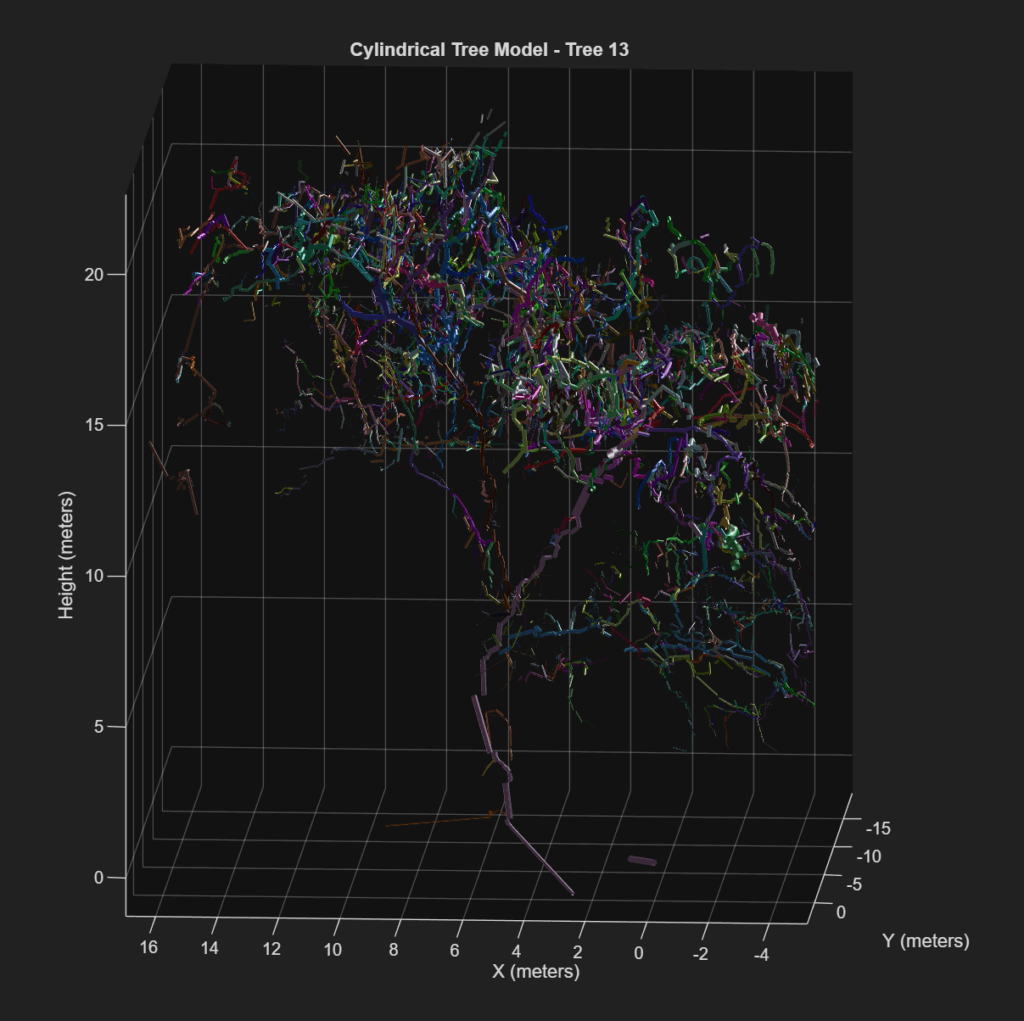

4. Results and Mapping of Hazard Potential

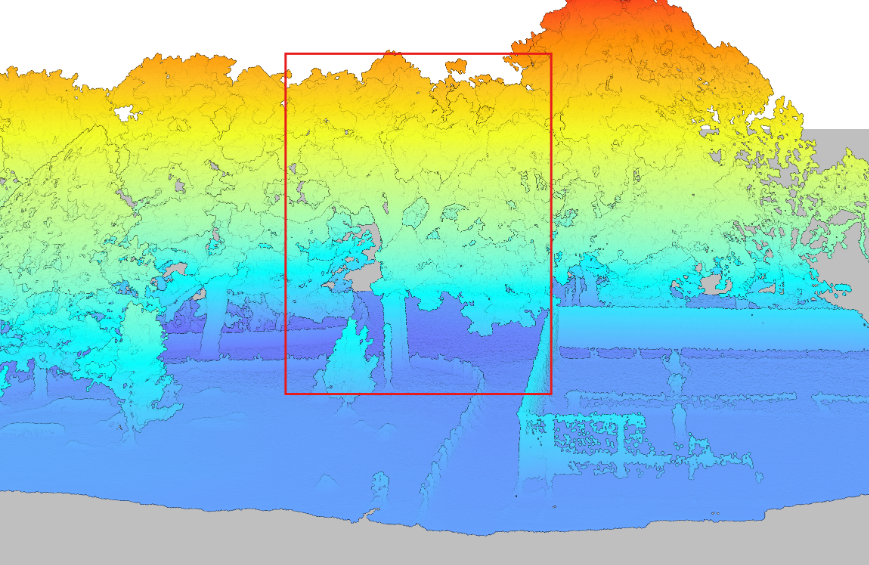

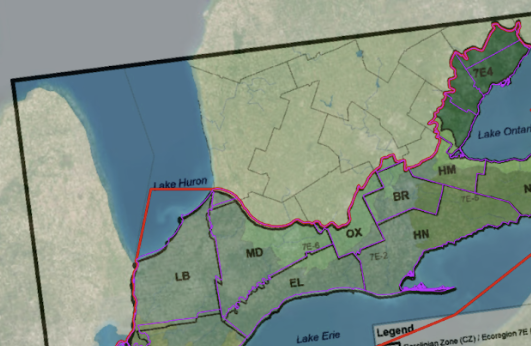

The final classification based on the HAZARD_DIR field (where 1 indicates a High Glare Hazard Potential) was used to generate a thematic map of the Mississauga road network. The map isolates the segments that will experience direct, high-intensity sun glare during the 4:00 PM EST winter commute.

4.1. Map Output Description

The map, titled “Solar Glare Hazard Map of City of Mississauga for the First Week of The Year,” clearly differentiates between segments with no glare hazard (yellow) and those with a high solar glare hazard (red).

• Yellow Segments (Street with no Solar Glare Hazard in first week of the year): These represent the vast majority of the network. They include roads running generally north-south (where the sun is primarily hitting the side of the vehicle) or segments where the driver is traveling away from the low sun angle (i.e., eastbound/northeast-bound traffic).

• Red Segments (Street with High Solar Glare Hazard in first week of the year): These are the critical segments for this analysis. They represent roads that are:

1. Oriented in the southwest-to-west direction (similar to the sun’s average azimuth).

2. Where a driver traveling along that segment would be facing directly into the low sun angle.

4.2. Analysis of Identified Hazard Corridors

The high-hazard (red) segments are predominantly clustered along major arterial roads as shown in the following map that follow a strong East-West or Northeast-Southwest orientation.

• Major Corridors: A highly concentrated linear feature of red segments is visible running across the northern/central part of the city, strongly suggesting a major East-West highway or arterial road where the vast majority of segments are oriented to the west. This confirms that these major commuter corridors are the highest-risk areas for this specific time and season.

• Localized Hazards: Several smaller, isolated red segments are scattered throughout the map. These likely represent the East-West portions of minor residential streets or short segments of angled intersections where the road azimuth briefly aligns with the sun.

• Mitigation Focus: The results provide specific, actionable intelligence. Instead of deploying wide-scale mitigation efforts, the city can focus on the delineated red corridors for strategies such as:

o Targeted message boards warning drivers during the specific 3:30 PM–5:00 PM time window in January.

o Evaluating tree planting or physical barriers only along these identified segments to block the low western sun.

5. Conclusion and Next Steps

The integration of solar geometry (Python/ArcPy) and directional filtering (Arcade) successfully generated a definitive dataset of high-risk road segments. The final map, generated based on the HAZARD_DIR field, clearly highlights specific routes that pose a safety risk to westbound or southwest-bound drivers during the target time window.

Future steps for this analysis include:

• Expanding the calculation to include the morning commute period (e.g., 7:00 AM EST) when the sun is low in the East/Southeast.

• Integrating the analysis with collision data to validate the modeled hazard areas.

• Developing mitigation strategies, such as targeted placement of tree cover or glare-reducing signage, based on the identified high-hazard segments.